Hydrology LIFE – towards wellbeing wetlands

Project results

After-LIFE Plan of the Hydrology LIFE Project (pdf, 8 Mb)

The results of the project have been published in a Layman´s Report.

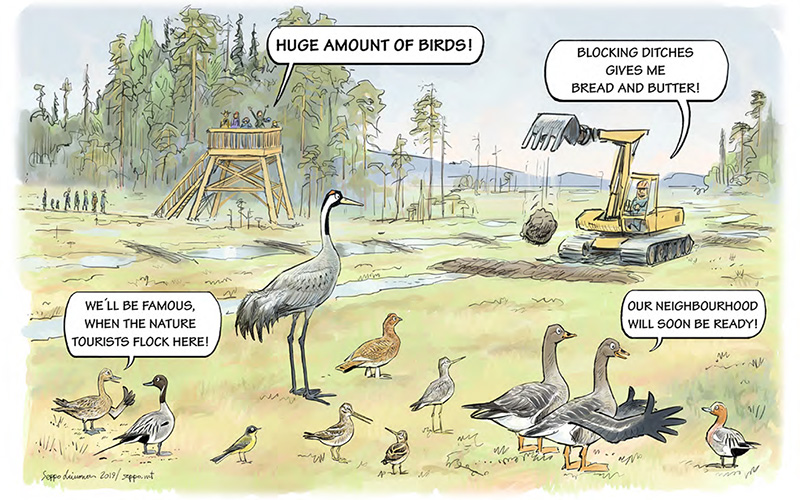

Hydrology LIFE was a large and effective project for improving the status of peatlands, important bird lakes and small water bodies in Finland.

Endangered natural peatlands and wetlands provide various benefits, including essential clean water circulation, bountiful berry-picking spots and rich bird habitats that bring joy to many.

Majority of peatlands in Finland are severely degraded by forestry-drainage, including also areas within Natura 2000 sites. Dredging, channelization and drainage are widely decreasing the ability of streams and ponds to sustain their natural communities and control the circulation of water.

In the Hydrology LIFE project (2017–2023), we restored valuable wetlands by blocking drainage ditches, returning diversity into small streams, preventing valuable bird lakes from overgrowth, and acquiring valuable peatlands for conservation. All the actions taken in the project contribute to the diverse wetland nature and species.

Wetlands are thriving at over hundred locations in Finland

The overall goal for peatland restoration has even been surpassed. A total of 5,800 hectares have already been restored, equivalent to over 8,000 football fields.

Technical monitoring at restoration sites ensures that restoration efforts have been as successful as planned.

Additionally, in multiple-use state forests of Metsähallitus, more than 200 hectares of peatlands have been restored.

The project employed over 100 contractors throughout Finland.

Project target areas (map, pdf).

Directing water to a dried-up mire has become an established restoration method

Water protection costs are also reduced by developing new, cost-effective methods for reconciling drainage ditching and restoration measures in commercial forests.

The Finnish Forest Centre and Tapio Ltd piloted rewetting cooperation in five protected peatlands. In the operational model, water is directed to a dried-up mire by digging ditches that allow water to reach the natural flow paths of the mire. Based on the experiences gained in the project, the operational model was updated. During the project, rewetting has become an established restoration method. New sites are being identified and implemented all around Finland.

Bird lakes and small streams now more diverse

The final restorations of small streams were completed during the autumn 2023. The restorations varied from a few hundred meters to several kilometres. For example, the Temmesjoki stream in Northern Ostrobothnia has been restored up to 4.6 kilometres. We have also restored small streams through volunteer work, which provides people an excellent opportunity to make significant contributions to nature conservation in good company. During the volunteer work, gravel beds were created in the streams, water was guided using dams, and rocks were added to the streams

By raising the water level, 14 lakes have been restored, and four lakes have undergone dredging and the addition of nesting islets.

Internationally remarkable monitoring!

We continued the long-term monitoring initiated in the Boreal Peatland LIFE project that ended in 2014. In our project, research was conducted to examine how the restoration measures carried out a decade ago have affected the vegetation and hydrology of the wetlands. Comprehensive monitoring shows that after restoration, the water levels and vegetation of the peatlands are gradually returning to their natural state. However, different types of peatlands react differently to restoration.

In addition, at the University of Oulu, drone monitoring methods have been developed for monitoring peatland restoration. Aerial images make it possible to assess how restoration has affected the area’s hydrology and vegetation. Images can show, for example, how the water levels surrounding the blocked ditches have started to rise and how vegetation has changed after restoration.

In 2023 we received results from bat monitoring at the University of Turku. Bat activity was monitored at 21 sites for four summers, both before and after restoration. The analysis of a vast amount of audio data revealed that bat activity increased, especially on restored mires. All bat species in Finland are protected, and the great result is that peatland restoration has no negative impact on these species, quite the opposite!

The monitoring of bird lake restorations has been conducted on all the restored lakes. Previous years’ monitoring has yielded pleasing results. Waterfowl have made the restored lakes their own.

Co-operation with project partners

The European Union has financed 60% of the Hydrology LIFE project’s budget of nearly nine million euros. This extensive collaborative project involved nine partners and over 200 experts.

The wide range of inventories and long-term monitoring by the project provide invaluable data on how restoration can be used to preserve the biodiversity, to improve water quality and to slow down climate change.

The information gained by examining how local people and the recreational users of protected areas feel about restoration can be used to develop restoration measures. The Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke) carried out an assessment of the socio-economic impacts of the project, such as examining restoration costs and regional economic effects. Luke also investigated how the restoration of biodiversity can improve water quality and the recreational and tourism value of the area. Based on surveys, citizens appreciate restoration work, and the benefits of restoration are considered greater than the costs.

Remote sensing provides huge possibilities for achieving data and results that cannot be reached by field work.

- Plans, reports and other materials delivered by the Hydrology LIFE Project are mostly in Finnish (pdf files) but some in English. The materials are on the Finnish project site.

- Read more about cooperation and networking

Wetland Game and Wetland Cards

In the WetlandGame, your task is to protect the vitality of nature and at the same time ensure people´s livelihood. The game is made for schoolchildren (age 12 or older) but int can be played by anybody.

We also published a set of Wetland Cards to give tips on how we all can help the wetlands and benefit from it, too.

Wetland cards are pdf files at the address julkaisut.metsa.fi

- Wetland card 1 Excessive water from forest to peatland

- Wetland card 2 Grazing animals help coastal meadows

- Wetland card 3 Help nature in the Wetland Game

- Wetland card 4 Peatland biodiversity benefits many

- Wetland card 5 Return brooks to the fish and anglers.

Project information

The project ran between 1st August 2017 and 31st December 2023.

The project was co-ordinated by Metsähallitus, Parks & Wildlife Finland.

Other beneficiaries included North Savo and Central Finland Centres for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment, Finnish Forest Centre, Tapio Oy, Natural Resources Institute Finland, Metsähallitus Forestry Ltd, and the universities of Jyväskylä, Oulu and Turku.

Project Manager was Maria Tiusanen

Metsähallitus, Parks & Wildlife Finland

maria.tiusanen@metsa.fi

The project has received funding from the LIFE Programme of the European Union. The material reflects the views by the authors, and the European Commission or the CINEA is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Last updated 19 July 2024